Lindee Abe, APRN

Measles is currently a hot topic, especially here in the Midwest. As of May 2025, we now have states to our north and south that have confirmed measles cases. When there isn’t an outbreak, measles is not commonly included in most differential diagnoses in urgent care, but now it should be considered for any flu-like symptoms or rash. As such, now is a good time to review what measles is, how to recognize it early, how to treat patients, and how to educate the public on their risk of contracting measles.

Epidemiology

Measles has been considered eliminated from the United States by the World Health Organization since 2000, meaning there was no continuous spread of the disease through natural transmission. Elimination does not mean there won’t continue to be sporadic disease outbreaks, which are currently occurring. The current outbreak in Texas started in a small Mennonite community in the western portion of the state with noted low vaccination rates. There have now been over 1,000 measles cases, and 11 states have active infections. This is the second largest outbreak since the disease was eliminated in 2000, with the outbreak of 2019 having around 1,200 cases. Based on the continued spread of the disease currently, we will likely surpass the numbers of the 2019 outbreak.

Measles Transmission

Measles is highly contagious, and roughly 95% of a community would have to be vaccinated against measles to prevent the spread in the community. The R0 of measles is between 12-18, higher than COVID-19, varicella, polio, and influenza. The measles virus is spread through airborne droplets and can live in the air and on surfaces for up to 2 hours after an infected person is present. This is significantly longer than other airborne diseases, like influenza, that typically only remain present for minutes to 1 hour after the infected person leaves the area. This is part of the reason for the high R0 of measles.

The other factor contributing to the high R0 is when the person is considered contagious. Patients with measles will generally be contagious 4 days before the rash’s onset and 4 days after the rash. The rash can sometimes only last 3 days, meaning it may resolve, and patients may think they are no longer contagious despite still being contagious for an additional 24 hours. The incubation period for measles is also longer, between 7 to 21 days, making it harder sometimes to solicit the correct history during the visit to determine if there was contact with an infected person. Most patients have difficulty remembering what they did for 14 days, 1-2 weeks before the visit. It is especially important to ask patients about their travel history to any area with current outbreaks.

Symptoms

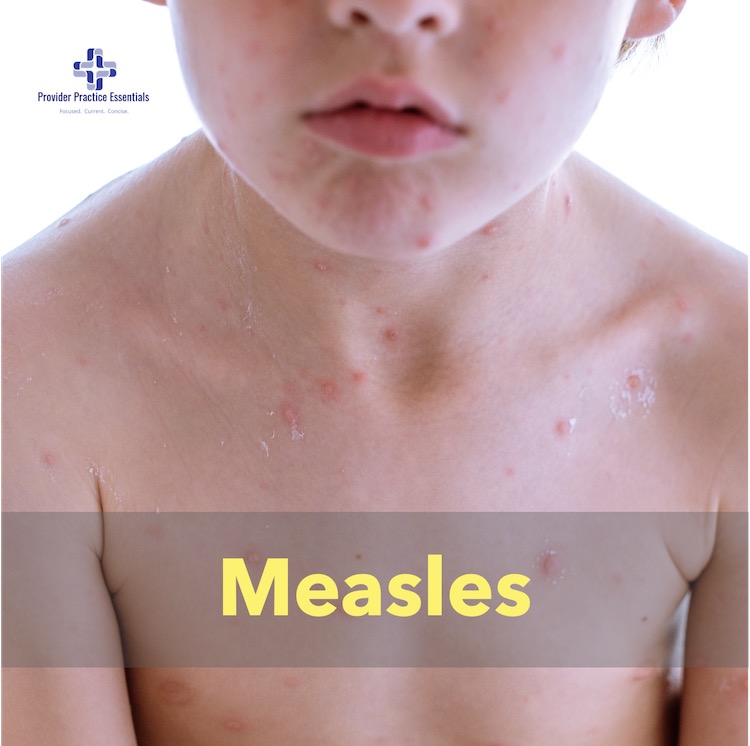

The initial symptoms of measles also make it difficult to detect initially. Most patients present with an influenza-like illness, which is often attributed to a viral infection in the winter months. Symptoms include a high fever (up to 104F), rhinorrhea, cough, and conjunctivitis. Koplik spots (i.e., white spots with an erythematous base on the inner cheeks in the mouth) appear several days after symptoms onset and are considered pathognomonic for measles infection. The rash typically appears 3-5 days after the initial symptoms and is described as a macular rash that starts on the face and spreads downward. It is sometimes referred to as a “Bucket of paint” rash because it can become confluent and spread as if a bucket of paint was poured over the person. The rash is typically not painful and is only mildly pruritic.

Diagnosis

Testing for measles generally involves a serum IgM test and a throat or nasopharyngeal swab for RT-PCR testing. It is also advisable to contact the local health department to clarify recommendations. The serum IgM test is the most commonly used test but can result in a false negative in the early days of the disease. The IgM test can remain positive for up to 30 days after the rash appears, whereas the RT-PCR test is generally only positive for 3 days after the rash onset. This results in the preferred test being dependent on where the patient is in the disease course to ensure the most accurate results.

Treatment

The treatment is supportive. Vitamin A has been shown to improve outcomes in some patients, but this is typically in patients who are vitamin A deficient. In the United States, vitamin A supplementation is generally only given to children who are inpatient with severe cases of measles. Complications from measles can include otitis media and diarrhea. There are more severe complications that are not as common but can still occur (e.g., pneumonia, encephalitis). The mortality rate of measles is higher in children, with a rate of 1 to 3 per 1,000 children. Additionally, 1 in 5 unvaccinated persons will require hospitalization.

Prevention

Vaccination for measles is essential to prevention. The measles vaccination was officially made available to the public in 1963. The Measles, Mumps, and Rubella (MMR) vaccine is highly effective with the recommended two-dose regimen. A single dose of the MMR vaccine provides 93% protection from measles, and a second dose increases that protection to 97%.

Between 1963 to around 1989, only one dose of the MMR vaccine was typically recommended. If the outbreak spreads, patients born during this period would likely need a second MMR vaccination. I also had a question from an older patient asking about the need for vaccination because they had not received it in childhood. However, the patient was born before 1957 and would be considered likely immune from having measles as a child. In questioning the patient, he couldn’t recall if he had measles but did remember that his three siblings all had it. I explained that with the R0 of measles, he likely was also infected at the same time. There is also the option to run a measles titer on patients unsure of previous infection or vaccination, but most insurances will not cover the cost.

Summary

Much more information is available about measles, and it is a fascinating disease. Measles is one of the only RNA viruses that hasn’t mutated to the point where a vaccine is no longer effective in preventing the disease. This also supports the need for vaccination. This was a quick update on some of the important things to consider as the outbreaks continue across the U.S. Hopefully, the number of measles cases will decline as we continue to discuss the importance of vaccination.

References:

Centers for Disease Control. (1989). Measles prevention: Recommendations of the Immunization Practices Advisory Committee (ACIP).

Retrieved from https://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/preview/mmwrhtml/00041753.htm#:~:text=A%20single%20dose%20of%20live,birthday%20needed%20to%20be%20revaccinated.

Gans, H., Maldonado, Y.A. (2025). Measles: Clinical manifestations, diagnosis, treatment, and prevention. Retrieved from https://www.uptodate.com/contents/measles-clinical- manifestations-diagnosis-treatment-and-

prevention?search=measles&source=search_result&selectedTitle=1~150&usage_type=d efault&display_rank=1#H3553254478

Guerra, F.M., Bolotin, S., Lim, G., Heffernan, J., Deeks, S.L., Li, Y., Crowcroft, N.S. The basic reproduction number (R0) of measles: a systematic review. Lancet Infect Dis. 2017 Dec;17(12):e420-e428. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(17)30307-9. Epub 2017 Jul 27. PMID: 28757186.

Public Health On Call. (2025). Controlling the Measles OUtbreak in the Southwest. Retrieved from https://publichealth.jhu.edu/2025/the-measles-outbreak-in-west-texas-and-beyond.

World Health Organization. (2024). Measles. Retrieved from https://www.who.int/news- room/fact-sheets/detail/measles.

World Health Organization. (n.d.). History of the measles vaccine. Retrieved

from https://www.who.int/news-room/spotlight/history-of-vaccination/history-of- measles-vaccination